Female Genital Mutilation (FGM)

Female genital mutilation (FGM) is defined as all procedures that involve partial or total removal of the external female genitalia, or other injury to the female genital organs for non-medical reasons (World Health Organisation, 2022). FGM is sometimes also known as female circumcision or cutting. Other local terms are tahoor, absum, halalays, khitan, ibi, sunna, gudnii, bondo and kutairi.

FGM is extremely painful and has serious consequences for physical and mental health. It can also result in death. FGM is considered child abuse in the UK and it is illegal to perform. It is also illegal to take a child abroad for FGM, even if legal in that country. FGM has significant long-term physical and emotional consequences for the survivors. It has been estimated that 137,000 girls and women in the UK are affected by this practice, but this is likely to be an underestimation.

FGM is sometimes incorrectly believed to be an Islamic practice. This is not the case and the Islamic Sharia Council, and the Muslim College and the Muslim Council of Britain (MCB), have condemned the practice of FGM.

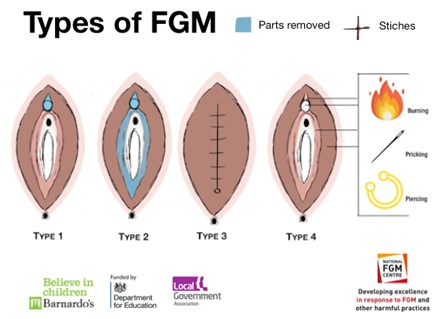

FGM is classified into four categories:

Type 1 Clitoridectomy: Partial or total removal of clitoris and/or prepuce.

Type 2 Excision: Partial or total removal of clitoris and labia minora, with or without excision of labia majora.

Type 3 Infibulation: Narrowing of the vaginal orifice with creation of a covering seal by cutting and repositioning the labia minora and/or labia majora, with or without excision of the clitoris.

Type 4 Other: All other harmful procedures to female genitalia for non-medical purposes including piercing, pricking, incising, scraping and cauterising.

The age at which girls undergo FGM varies enormously according to the community. The procedure may be carried out when the girl is new-born, during childhood or adolescence, just before marriage or during the first pregnancy. However, the majority of cases of FGM are thought to take place between the ages of infancy and 15 years of age (NHS Digital, 2022) and therefore girls within that age bracket are at a higher risk.

References

World Health Organisation (2022). Female Genital Mutilation – Key Facts

NHS Digital (2022). Female Genital Mutilation – Overview

FGM Centre (2022). Types of FGM

It has been estimated that 137,000 girls and women in the UK are affected by this practice, but this is likely to be an underestimation. FGM is thought to affect over 200 million women and girls worldwide with more than three million girls estimated to be at risk of FGM annually.

Local Prevalence

The ‘Prevalence of Female Genital Mutilation in England and Wales: National and Local Estimates’ (City University London, 2015), estimated the number of cases of FGM in Hampshire to be 344. Of these, 27 are in girls under the age of 15. Prevalence rates vary across the local area, from 0.3 per 1000 population in Havant, New Forest and Test Valley to 2.5 per 1000 in Portsmouth and 3.0 in Southampton. Basingstoke and Deane have a prevalence of 1.1 per 1000. Rushmoor is estimated to have a prevalence of 0.9 cases per 1000 population.

Many communities practice FGM, but those at particular risk in the UK originate from:

- Somalia

- Egypt

- Sudan

- Sierra Leone

- Eritrea

- Gambia

- Ethiopia

References

City University London (2015). Prevalence of Female Genital Mutilation in England and Wales: National and Local Estimates

FGM is carried out in communities across the world, including the UK, for various cultural, religious and social reasons within families and communities. It is carried out in the mistaken belief that it will benefit the girl in some way (for example, as a preparation for marriage or to preserve her virginity). However, there are no acceptable reasons that justify FGM. It is a harmful practice that has no health benefits.

The causes of female genital mutilation include a mix of cultural, religious and social factors within families and communities. Where FGM is a social convention, the social pressure to conform to what others do and have been doing is a strong motivation to perpetuate the practice. FGM is often considered a necessary part of raising a girl properly, and a way to prepare her for adulthood and marriage.

FGM is often motivated by beliefs about what is considered proper sexual behaviour, linking procedures to premarital virginity and marital fidelity. In many communities, FGM is believed to reduce a woman’s libido and is therefore believed to help her resist “illicit” sexual acts. When a vaginal opening is covered or narrowed, the fear of the pain of opening it, and the fear that this will be found out, is expected to further discourage “illicit” sexual intercourse among women with this type of FGM.

FGM is associated with cultural ideals of femininity and modesty, which include the notion that girls are “clean” and “beautiful” after removal of body parts that are considered “male” or “unclean”.

Girls from a variety of religious backgrounds are affected by FGM as it is a social custom. It is important to note that no religious scripts prescribe the practice. However, practitioners often believe the practice has religious support. Religious leaders take varying positions with regard to FGM: some promote it, some consider it irrelevant to religion, and others contribute to its elimination. Local structures of power and authority, such as community leaders, religious leaders, circumcisers, and even some medical personnel can contribute to upholding the practice.

In most societies, FGM is considered a cultural tradition, which is often used as an argument for its continuation. In some societies, recent adoption of the practice is linked to copying the traditions of neighbouring groups. In some cases, it has started as part of a wider religious or traditional revival movement. In some societies, FGM is practised by new groups when they move into areas where the local population practise FGM.

Professionals should be aware of the signs and indicators below that may indicate that a child is at risk of female genital mutilation:

- A relative or someone known as a ‘cutter’ visiting from abroad.

- A special occasion or ceremony takes place where a girl ‘becomes a woman’ or is ‘prepared for marriage’.

- A female relative, like a mother, sister or aunt has undergone FGM.

- A family arranges a long holiday overseas or visits a family abroad during the summer holidays.

- A girl has an unexpected or long absence from school.

- A girl struggles to keep up in school.

- A girl runs away – or plans to run away – from home.

Professionals should also be aware of the signs and indicators below that may suggest that FGM has taken place:

- Having difficulty walking, standing or sitting.

- Spending longer in the bathroom or toilet.

- Appearing quiet, anxious or depressed.

- Acting differently after an absence from school or college.

- Reluctance to go to the doctors or have routine medical examinations.

- Asking for help – although they might not be explicit about the problem because they are scared or embarrassed.

References

NSPCC (2022) Female Genital Mutilation – Signs of FGM

There are no health benefits to FGM and it can cause serious harm, including:

- Constant pain.

- Pain and difficulty having sex.

- Repeated infections, which can lead to infertility.

- Bleeding, cysts and abscesses.

- Problems peeing or holding pee in (incontinence).

- Depression, flashbacks and self-harm.

- Problems during labour and childbirth, which can be life threatening for mother and baby.

Some girls die from blood loss or infection as a direct result of the procedure.

FGM and sex

FGM can make it difficult and painful to have sex. It can also result in reduced sexual desire and a lack of pleasurable sensation.

A girl or woman can talk to their GP or another healthcare professional if they have sexual problems that they feel may be caused by FGM. The GP can refer the girl or woman to a special therapist for further support. In some cases, a surgical procedure called a deinfibulation may be recommended, which can alleviate and improve some symptoms.

FGM and pregnancy

Some women with FGM may find it difficult to become pregnant, and those who do conceive can have problems in childbirth.

When a girl or woman is expecting a baby, their midwife should ask if they have had FGM at the antenatal appointment.

It is important for a girl or woman to tell their midwife if they think this has happened to them, so that the midwife can arrange appropriate care.

FGM and mental health

FGM can be an extremely traumatic experience that can cause emotional difficulties throughout life, including:

- Depression

- Anxiety

- Flashbacks to the time of the cutting

- Nightmares and other sleep problems

In some cases, women may not remember having the FGM at all, especially if it was performed when they were an infant.

References

NHS Digital (2022) Female Genital Mutilation – Overview

The Multi-Agency Statutory Guidance on Female Genital Mutilation, issued under Section 5C of the Female Genital Mutilation Act, is for all persons and bodies in England and Wales who are under statutory duties to make arrangements to discharge their functions having regard to the need to safeguard and promote the welfare of children and vulnerable adults. It was first published in 2016 and later updated in July 2020. The multi-agency guidance should be read alongside other safeguarding guidance, including (but not limited to):

- Working Together to Safeguard Children (2018) in England

- Safeguarding Children: Working Together under the Children Act 2004 (2007) in Wales

The multi-agency guidance places a duty on all regulated professionals within health, social care and teachers to report ‘known’ cases of FGM in girls under 18 years of age to the police. This applies where in the course of professional duties, a regulated professional is informed by a girl under 18 years that FGM has been carried out on her; or observes physical signs which appear to show FGM has been carried out on a girl under 18 years.

This is a legal duty to share which allows the common law of confidentiality to be set aside. The duty is a personal responsibility, which requires the individual professional who becomes aware of the case to make a report. The responsibility cannot be transferred. It is the duty of the professional who identifies FGM and/or receives the disclosure to do the reporting at the time.

The referring professional needs to telephone the police (on 101) to make a report and complete an Inter-agency referral form before close of practice the following day. The following information should be accurately recorded:

- Girl’s name, DOB, address.

- Your contact details.

- Your safeguarding lead’s details.

Professionals should remember to document all decisions and actions and involve the GP, school nurse and health visitor by contacting them directly by telephone or email. It remains best practice to share information between healthcare professionals to support the ongoing provision of care and efforts to safeguard women and girls against FGM. For example, after a woman has given birth, it is best practice to include information about her FGM status in the discharge summary record sent to the GP and health visitor, and to include that there is a family history of FGM within the Personal Child Health Record (PCHR), often called the ‘red book.’

Professionals should establish if there are any young female children within the family or if an expected baby is female, as practitioners have a legal and moral obligation to protect them from FGM. Any child with a family history of FGM must have an alert added to their health record on FGM-IS, which is an FGM information service. This is an IT system which supports ongoing safeguarding of females under the age of eighteen who have a family history of FGM (NHS Digital, 2021).

References

NHS Digital (2021) Female Genital Mutilation – Information Sharing

4LSAB and 4LSCP Multi-Agency Guidance on ‘Honour’ Based Abuse, Forced Marriage and Female Genital Mutilation – A multi‐agency guidance document for agencies and organisations to use with cases or suspected cases of ‘honour’ based abuse in Hampshire, Portsmouth, Southampton and the Isle of Wight.

Forced Marriage and Learning Disabilities: Multi-Agency Practice Guidelines – These practice guidelines have been developed to assist professionals encountering cases of forced marriage of people with learning disabilities.